However, the alien theory won’t gain any credibility unless the signal can be replicated, and so far, efforts to detect the signal again have been unsuccessful.Late one night in the summer of 1977, a large radio telescope outside Delaware, Ohio intercepted a radio signal that seemed for a brief time like it might change the course of human history. None of the numerous other theories could prove conclusively that this signal wasn’t of intelligent alien origin either. Thirdly, the twinkling of astronomical bodies, called interstellar scintillation, was thought of as an explanation, but other more sensitive telescopes that were built to detect such signals have not. But this would have to mean that the space debris was still in space relative to the telescope. Secondly, Ehman had said that it was likely a signal emitted from earth reflected off a bit of space debris. It was not used for human transmission, and didn’t come from a known planet or asteroid in that position. Firstly, the frequency that the signal was transmitted in was a rarely used one. This signal still doesn’t have an explanation, although several theories have been put forth (and rejected). This precession can be heard for each interstellar hydrogen and interstellar hydroxyl, at 1.42 GHz and 1.66 GHz respectively.Ī waterhole is significant because of the presence of hydrogen and hydroxyl, both components of water, whose presence increases the probability of habitability. This is called precession and occurs in planets as well. A proton, as it spins and wobbles around its axis, would draw a circle in the air if extended. Above 10 GHz, there is greater noise from the tiniest of sub atomic particles, whose whizzing becomes loud.Īlso, there are ‘waterholes’ in space, where there is abundance of hydrogen and hydroxyl (OH). It turns out that below 1Ghz, there is a lot of noise in the galaxy emitted by astronomical bodies, making it hard to identify a particular signal. It is transparent to only two frequencies of electromagnetic radiation: the visible spectrum, enabling us to see sunlight and starlight directly, and the 1 to 10 Ghz gap. Our atmosphere acts as a thick cover filtering out a large selection of frequencies. Then there’s the physical hurdle of interplanetary dust and planetary atmosphere.

Analysing dataįor an alien to contact humans, they would have to transmit their signals at frequencies they know will be heard.Īs mentioned above, the most obvious choice of frequency would be to use hydrogen as it had the highest probability of being recognised. The Big Ear telescope has since been decommissioned and disassembled. The antenna was pointed at the same angle for several days and then titled slightly so that it could scan the next band of sky around the earth.Īny point in the sky would be in the telescope’s range for 72 seconds only because that’s how long signals can still be accessible through reflection from the antenna’s giant dish.Īll data received that night was printed on paper since there was no digital storage facility back in 1977. As the earth rotated, the telescope’s antenna swept through the night sky, listening for signals coming from various directions. The Wow! Signal was recorded for 72 seconds, an incoming signal’s maximum duration of detection. And since hydrogen is the most common element in our universe, it was considered highly likely that intelligent life outside of the earth would be familiar with it. The 1.42 GHz radio frequency is naturally emitted by hydrogen. One of the reasons why this signal has been such a fixation among science enthusiasts is because the Big Ear radio telescope was specifically built to function on a frequency speculated to be the one in which aliens would communicate. But it remains the strongest candidate for alien radio transmission that scientists have received so far.

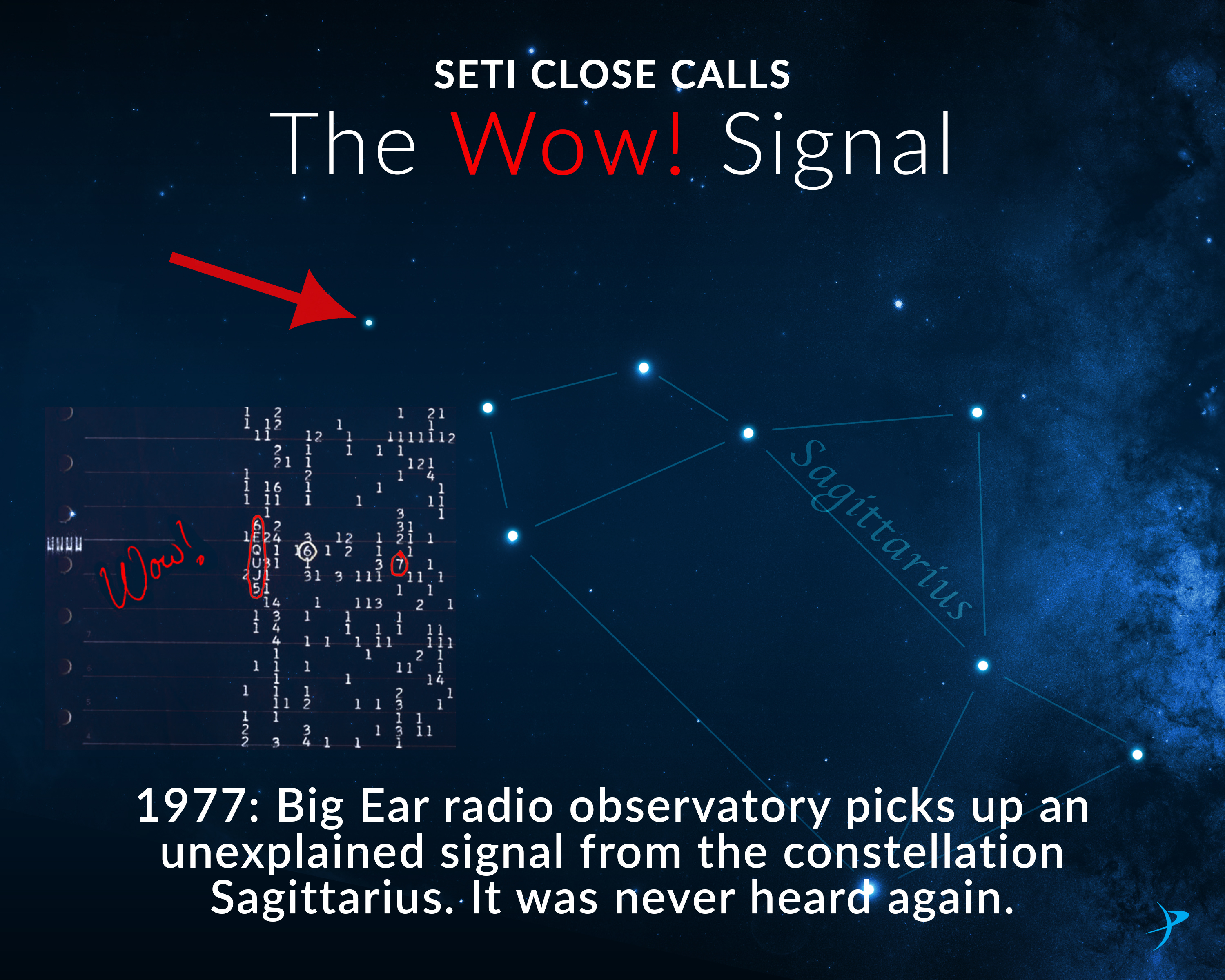

The signal has not been decoded, or detected again. A scanned copy of the original computer printout on which Ehman wrote the word Wow! | Commons The incident came to be known as the ‘Wow! Signal’ and has since been used to support the argument to search for alien civilisations. This powerful blast of radio waves had arrived from the direction of the constellation Sagittarius and bore all the hallmarks of extraterrestrial origin. Mystified, Ehman circled it on the readout and wrote: “Wow!”.

He received one that looked very much like it was from aliens. Bengaluru: On 15 August, 1977, US astronomer Jerry Ehman was using the Ohio State University’s Big Ear radio telescope to scan the sky for possible signals from extraterrestrial intelligence.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)